History has a strange way of remembering nations under siege. The conqueror’s story is carved in stone, the victim’s in silence. But for Palestine, one man refused that silence — Mahmoud Darwish, the poet who made the world listen even when it wanted to turn away.

Born on March 13, 1941, in the Galilean village of al-Birwa, Darwish’s first memories were not of harvest seasons or schoolyard laughter but of displacement. In 1948, when Israeli forces razed his village during the Nakba, his family fled to Lebanon. A year later, they returned to find al-Birwa gone — erased from the map, rebuilt as someone else’s home. That absence, that theft of belonging, would become the heartbeat of his life’s work.

Darwish’s story is not just a poet’s biography. It is the compressed history of Palestine itself — the land lost, the exile endured, the identity carried like an heirloom. His verses became the currency of memory, traded from one refugee camp to another, reminding his people that to name their homeland was to keep it alive.

From Censorship to Global Recognition

Darwish began publishing poetry as a teenager in Haifa, his words laced with defiance. As editor of Al-Jadid, the literary magazine of the Israeli Communist Party, he gave space to Palestinian voices long suppressed under military rule. He was arrested multiple times for his political activism — proof that in occupied lands, even a poem can be treated like a weapon.

In 1971, he left Israel to study in Moscow, and from there moved to Cairo and Beirut. His pen, however, never strayed far from Palestine. Joining the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1973, he became not just a literary figure but a political one, eventually drafting the 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence. Yet he was never afraid to disagree with his own leadership. In 1993, he resigned from the PLO’s Executive Committee, denouncing the Oslo Accords as a compromise that gave away too much for too little. For Darwish, truth was worth more than political convenience.

You May Like To Read: The High-Tech Programme Transforming Punjab’s Crime Scene

The Poetry of Identity

Darwish’s most famous early work, Identity Card (1964), was a blunt declaration:

“Write down!

I am an Arab

And my identity card is number fifty thousand…”

It was not mere protest — it was reclamation. In a world determined to strip Palestinians of name, place, and dignity, Darwish catalogued them line by line. His poetry became both shield and mirror: a defense against erasure and a reflection of a people’s resilience.

Yet Darwish was not only the poet of slogans and street chants. As he matured, his work moved towards the universal. In A Lover from Palestine, he used the imagery of love to describe a homeland — the color of wheat, the scent of earth, the warmth of the morning sun. In In the Presence of Absence, written later in life, he confessed to learning “to love what I have lost, and to be a stranger to what I have found.” His words carried the Palestinian cause far beyond the geography of the conflict; they turned it into a human story that could belong to anyone who has ever been displaced.

Exile as a Permanent Address

For Darwish, exile was not just a political condition — it was an emotional and spiritual state. Even when he returned to the West Bank in 1996, settling in Ramallah, he understood that the return was never complete. His home village remained rubble, his people still scattered. The exile had simply shifted from physical to psychological.

You May Like To Read: Govt Announces Plan to Privatize 24 State-Owned Entities Over 5 Years

This is perhaps why his work resonates so deeply — because it speaks to a loss that is at once personal and collective. His verses echo the Palestinian experience of living in one place while belonging to another, of building homes in temporary spaces, of dreaming in the language of a vanished childhood.

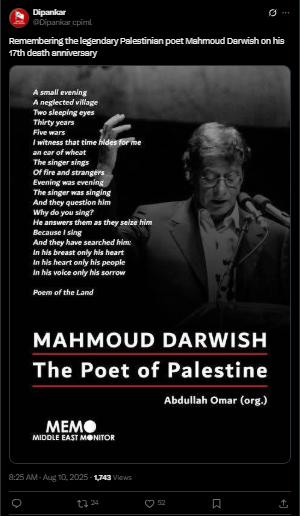

A Funeral for the Nation’s Heart

Mahmoud Darwish died on August 9, 2008, in Houston after heart surgery. His body was flown to Ramallah, where thousands lined the streets. President Mahmoud Abbas declared three days of mourning. In that moment, Palestine buried more than a poet; it buried a part of its voice.

The images from that day — the coffin draped in the Palestinian flag, the slow cortege moving through Ramallah, the sea of mourners — were a reminder that Darwish belonged to everyone. He was not only the property of literary circles or political elites. He was the poet of farmers and fighters, mothers and refugees, children who had never seen the towns their parents still called “home.”

You May Like To Read: Can Punjab’s Water Strategy Save Pakistan from a Thirsty Future?

Why Darwish Matters Now

In today’s Palestine, where blockades turn cities into prisons and the world’s attention drifts elsewhere, Darwish’s poetry remains a stubborn act of survival. His verses tell us that occupation is not only a military act but also an attempt to rewrite memory. By writing, he preserved the unedited Palestinian story — a story not told in the language of the occupier, but in the tongue of those who still dream in Arabic.

For Pakistanis, there is a lesson in Darwish’s life and words. Nations survive not only by defending borders but by defending narratives. Darwish understood that the erasure of history begins with the silencing of voices. His work insists that the first duty of a people under siege is to keep speaking, keep remembering, and keep imagining freedom — even when freedom seems impossibly far.

Source: X/@Dipankar_cpiml

The Enduring Verse

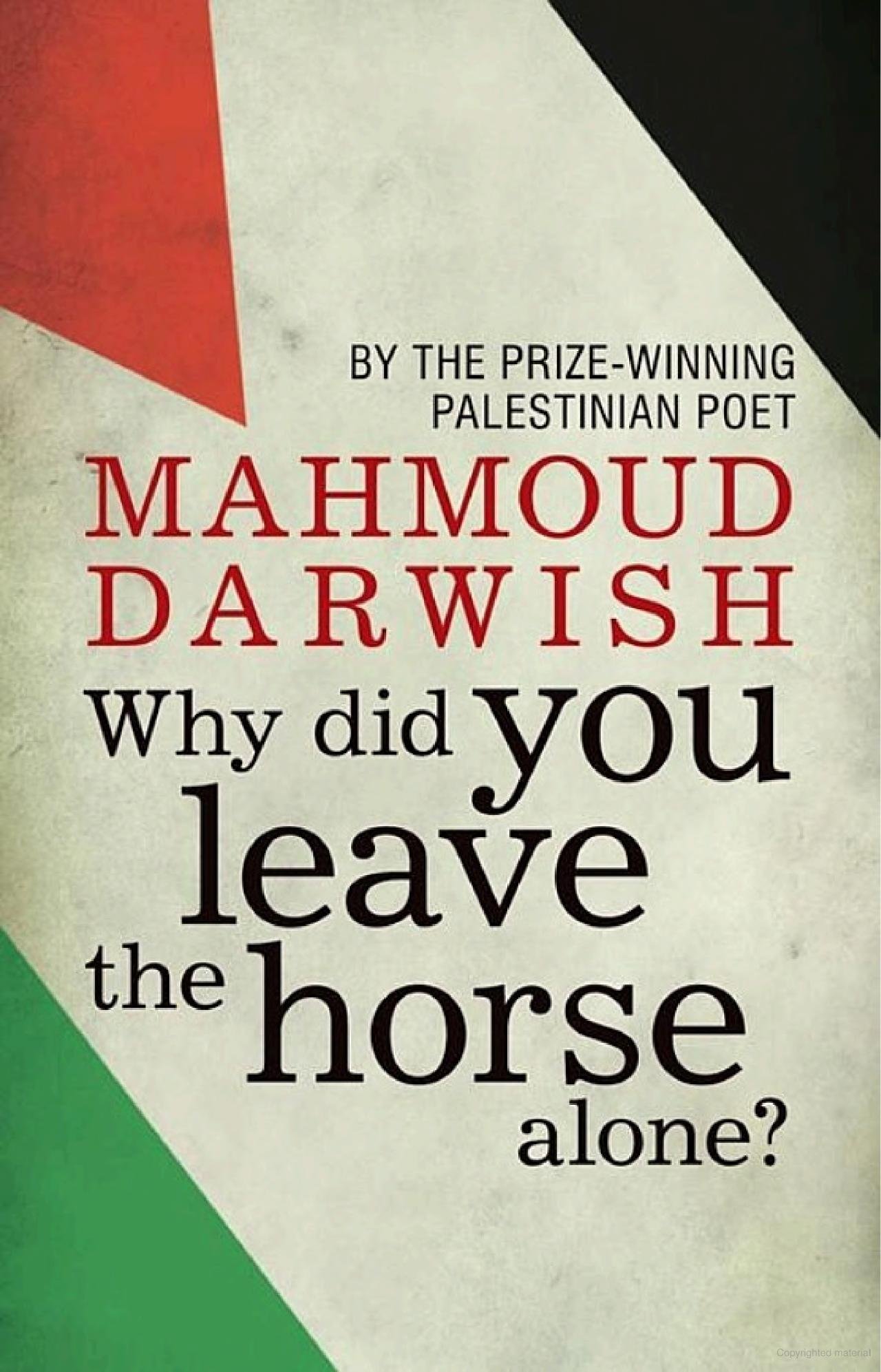

Mahmoud Darwish wrote more than thirty volumes of poetry and eight books of prose. His work has been translated into over twenty languages. But translation can only carry so much; the full power of his poetry lives in the rhythms of Arabic, where the homeland is never just a place, but a mother, a lover, a memory, and a prayer.

Today, whether read in a café in Ramallah, whispered in a Gaza hospital, or recited at a solidarity rally in Lahore, his words still move like quiet resistance through the air. They remind us that occupation can take land, homes, even lives — but it cannot take the music of a people’s voice.

Mahmoud Darwish once said, “We have on this earth what makes life worth living.”

For Palestine, his poetry is one of those things.

And for the rest of us, it is a reminder that the most powerful borders are drawn in the human heart — and that they, too, are worth defending.