The Taliban’s return to power in August 2021 placed Pakistan in a difficult position. Islamabad has long influenced Kabul, from the Taliban’s first rule to their insurgency years. Today, it faces both opportunities and risks. Pakistan has hosted diplomats, opened supply routes, backed reconstruction projects, and joined trilateral talks with China. Yet challenges remain. Security threats, refugee flows, and insurgent sanctuaries strain ties. Regional rivalries deepen mistrust. Pakistan’s engagement since 2021 shows efforts at diplomacy and stability, but obstacles continue to limit its influence.

You May Like To Read: Pakistan’s New Consulate in Kandahar: Soft Power or Security Outreach?

Mediation and Diplomatic Engagement

Pakistan has attempted to improve its relationships with the new Afghan government but, it has not recognized it. In 2025, Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar announced that Islamabad would deploy an ambassador to Kabul. It was the initial such movement since the U.S. withdrawal and indicated a defrosting of relations. Now the embassy is headed by an ambassador rather than by a charge d’affaires. Similar steps have been taken by China, the UAE, and Uzbekistan. In May 2025, China organized an informal trilateral meeting. The foreign ministers of Afghanistan and Pakistan have agreed on the exchange of ambassadors. They also made commitments to deepen diplomatic, trade, and transit relations. This momentum was welcomed by a statement made by the Foreign Office in Pakistan. It emphasized strategies of improved diplomacy, trade, and transit facilitation with Kabul.

Pakistan-Afghanistan relations are on positive trajectory after my very productive visit to Kabul with Pakistan delegation on 19th April 2025. To maintain this momentum, I am pleased to announce the decision of the Government of Pakistan to upgrade the level of its Chargé…

— Ishaq Dar (@MIshaqDar50) May 30, 2025

Pakistan has attempted to mediate between the Afghanistan groupings and international actors. Before the Taliban’s rise to power, it facilitated talks like the Doha process. Following 2021, Islamabad received Afghan interlocutors and demanded inclusive governance. According to analysts, Pakistan has a critical interest in a resolution that can guarantee stability in the region. Reports claim it enabled talks in 2022 between Taliban leaders and minority figures in Qatar and Abu Dhabi. Islamabad officials argue that they continue to support intra-Afghan talks and encourage the Taliban to establish a broader government.

Security Challenges and Pressure

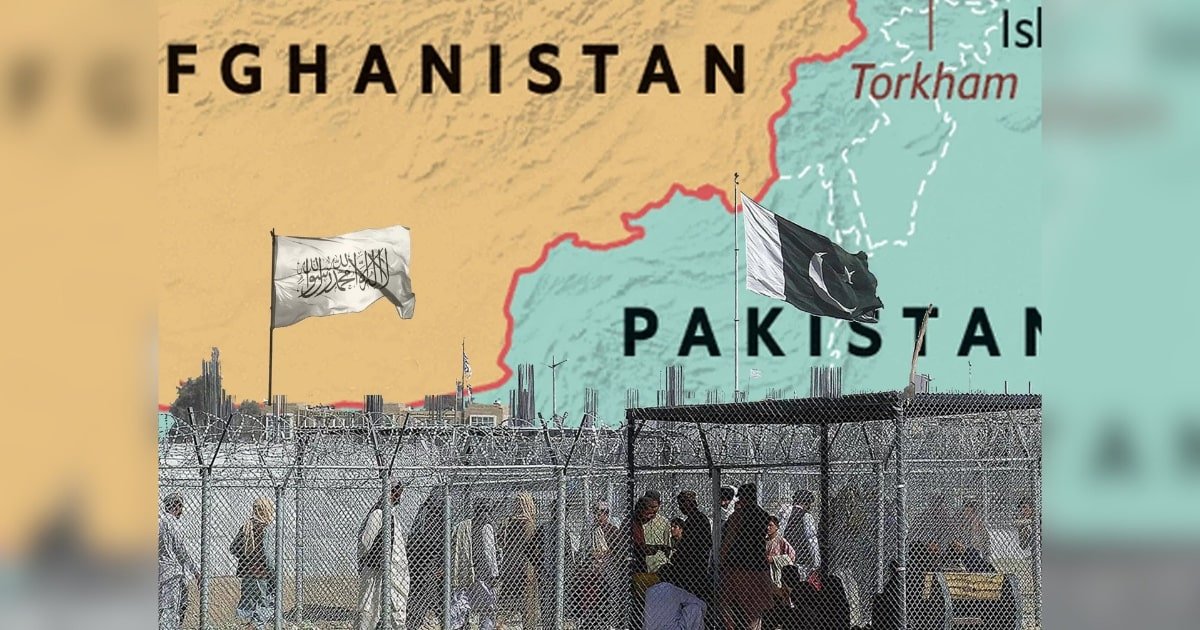

Security challenges dominate Pakistan’s Afghanistan policy. Islamabad has long accused militant groups, especially the FAK, of using Afghan soil. In November 2023, caretaker Prime Minister Anwarul Haq Kakar openly blamed the Taliban for enabling terrorism. It marked a sharp shift from Pakistan’s earlier softer stance. The statement followed a surge of militant attacks inside Pakistan, with over 2,800 fatalities since 2021. Officials linked these attacks to a Taliban shelter for the TTP. To respond, Islamabad launched a pressure campaign. It ordered 1.7 million undocumented Afghan refugees to leave starting in late 2023. Trade and aid flows were also reduced. Analysts said Pakistan was imposing economic pain on the Taliban by cutting commerce and transit. Pakistan even announced it would not lobby for Taliban recognition abroad. This change showed rising frustration, with Kakar warning that peace in Afghanistan had become a nightmare for Pakistan.

Source: USIP

Border security has also grown tense. In December 2024, Pakistani forces struck militant hideouts in eastern Afghanistan. Afghan officials reported civilian casualties, including women and children, sparking protests. Pakistan called the strikes counterterrorism, while Kabul denounced them as violations of sovereignty. Both sides trade accusations: Kabul claims militants are a domestic Pakistani problem, while Islamabad insists Afghan land is used for cross-border attacks. These tensions highlight mistrust on both sides. They also show that Pakistan’s peace-brokering role is weakened by its security concerns and domestic pressures.

Source: Aam Awam

Economic and Regional Cooperation

Pakistan has sought to revive trade and transit with Afghanistan. Both sides agreed to improve border infrastructure and simplify customs. In 2025, Pakistani officials welcomed Chinese-backed projects and joined talks on energy and transport in Beijing. Islamabad pledged support for Afghan reconstruction and promised to expand export access through ports and railways. Proposals include joint industrial zones near the border and pipeline extensions under the TAPI project. These steps aim to deliver mutual economic benefits.

Source: Reuters

Yet progress remains difficult. By mid-2025, sanctions and donor fatigue had left Afghanistan struggling. Pakistan tied trade and transit access to counterterrorism cooperation. Although bilateral trade grew to nearly $1 billion in the first half of 2025, persistent militant attacks by the FAK remain a major obstacle to further economic relations. Pakistan has imposed a 10% fee on Afghan imports via its ports, interpreted as economic leverage to pressure the Taliban to curb such militant activity. Its stance showed that without Taliban action against militancy, economic ties will stay limited. Chinese and Gulf investment also depends on stability, which Pakistan alone cannot ensure. Thus, while Islamabad speaks of commerce as a tool for peace, security concerns still dominate its policy.

Assessment: Stability or Standoff?

Pakistan’s approach has produced mixed results. On the positive side, it has avoided a complete breakdown in relations. Ambassadors have been reappointed and dialogue channels remain open. Security talks with the Taliban show Pakistan trying to stabilize the region. Some cross-border trade has resumed, and joint infrastructure discussions point to future cooperation.

But deep problems persist. Punitive tactics like refugee expulsions and trade curbs have hurt Afghans and fueled resentment. The FAK remains active, and violence inside Pakistan continues despite pressure on Kabul. Mediation for inclusive governance has failed, as the Taliban refuse to share power. Many Afghans distrust Islamabad, viewing it as self-interested rather than neutral.

Globally, Pakistan’s image is also mixed. It won credit for evacuations and humanitarian aid, but critics accuse it of double-dealing. Islamabad supports reconstruction in words while allegedly backing proxies in practice. Its new hard line, pressuring the Taliban and refusing to lobby for them, has unsettled Kabul. Domestic outrage over terror attacks further constrains Pakistani leaders, making long-term compromise harder.

In summary, Pakistan can shape Afghanistan’s direction but cannot deliver lasting peace alone. Its policy mixes engagement and coercion. Diplomatic upgrades and trade talks show cooperation, while refugee expulsions and military strikes show pressure. Analysts argue Pakistan’s role is important but insufficient without regional consensus and Taliban reforms. Its actions have pushed Kabul to consider Pakistan’s security needs, yet stability remains elusive.

True peace will need more than Islamabad’s efforts. It depends on Taliban governance, Afghan political inclusion, and coordination among regional powers. Pakistan’s influence rests on balancing security concerns with support for reconstruction and rights. For now, it is a central player but not a guarantor. Its legacy is still unfolding. Engagement and coercion keep it relevant, but the outcome may be either a fragile truce or a step toward lasting peace.

You May Like To Read: Pakistan and the Fallout of the U.S. Withdrawal from Afghanistan