The Siachen theatre has always been a challenging and unpredictable one. While Force Command Northern Areas (FCNA) has become battle-hardened by gaining ample experience in high-altitude warfare, the Glacier itself has its mysterious ways. Despite numerous precautions, life in Siachen always keeps one on one’s toes. It is a well-known fact that the terrain is not fit for human survival, and yet Pakistan maintains its military presence to safeguard the sovereignty of its motherland. Post-1984 conflict, aside from a few skirmishes here and there, the battle has always been against nature. The Glacier has deep crevices, air pockets, and moving water deep underneath it. Most soldiers and officers stationed at Siachen have also reported movement of the Glacier under their feet. While quite a number of men have been lost to hypothermia, high-altitude cerebral edema, as well as frostbite, the number was never as high as in the Gyari incident.

Geo-Strategic Significance of Gyari

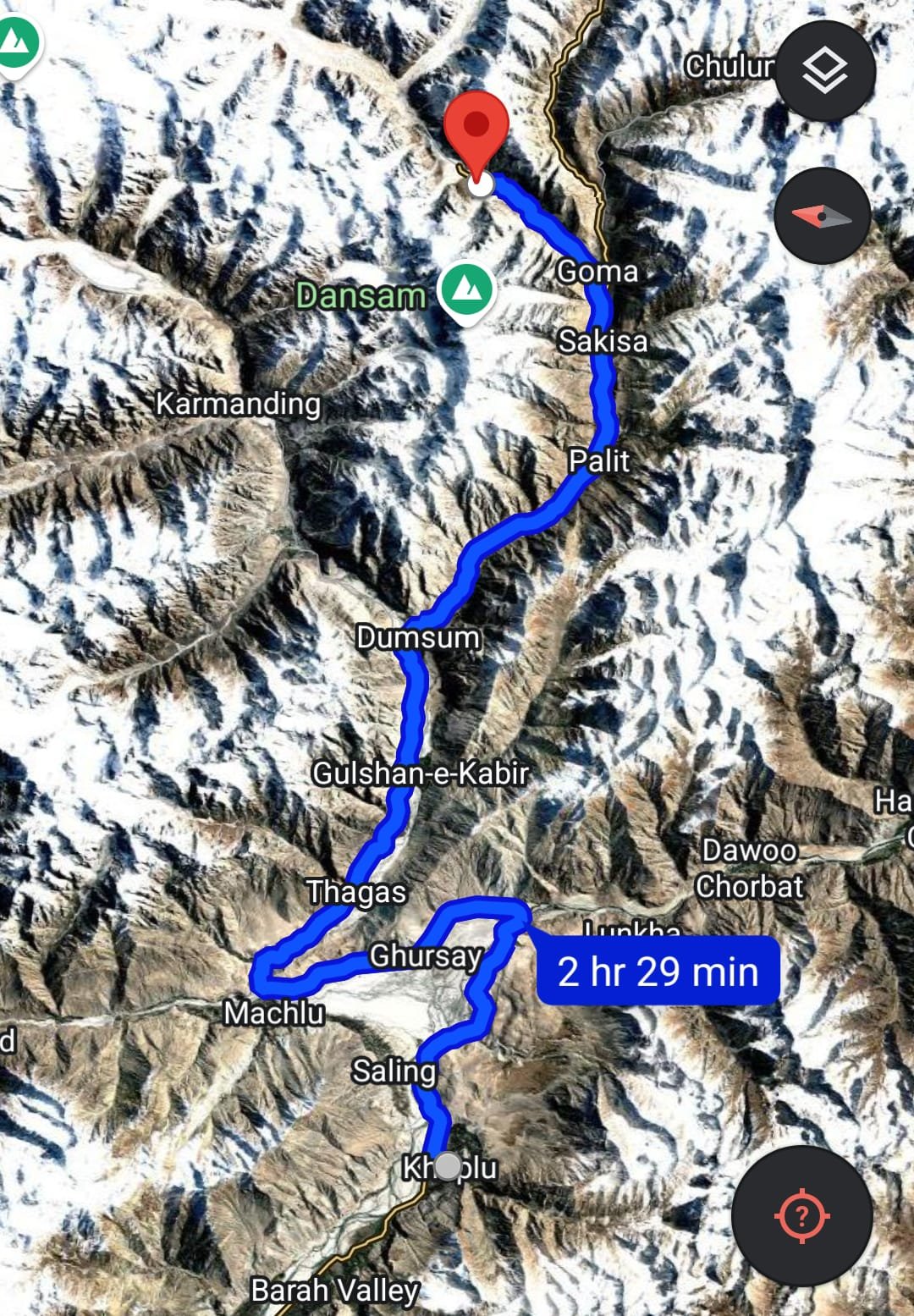

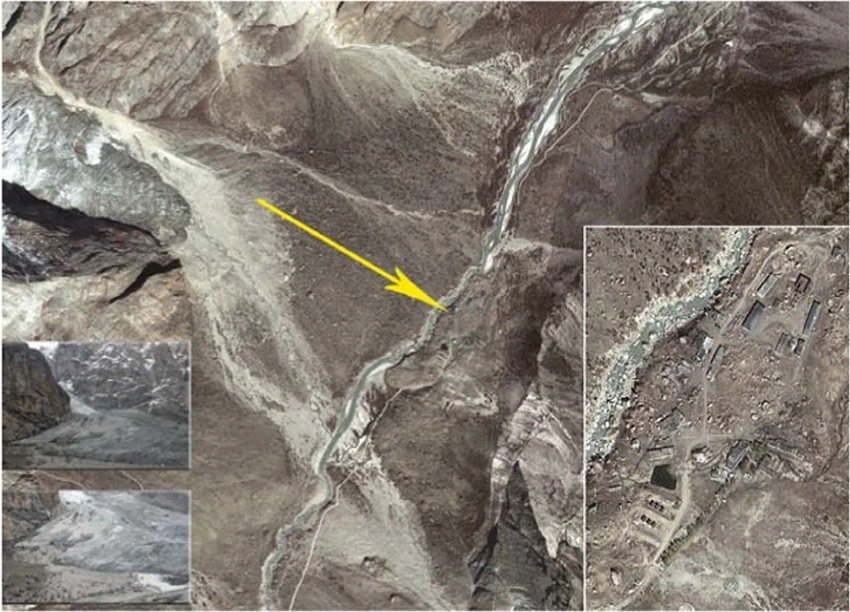

Before the Gyari incident occurred, the standard route of access to Siachen passed through Khaplu, Dumsum, and Goma to Gyari. Gyari was the last battalion-sized establishment from where men and supplies used to head over to the actual Glacier. All communications to forward posts on Siachen were controlled from Gyari and sent back to Goma. It was also the stop where troops stayed to acclimatize to the altitude before heading further up to the Glacier in small parties linked together by ropes. It still remains a dominant ridgeline through which the Chulung River passes. Troops stationed at Sia La and Bilafond La would rest here on their way to their posts. Gyari had remained the battalion headquarters and the first sign of human civilization for troops coming down from Siachen ever since 1984. Any development on the glacial front would reach here first and then disseminate further, making it a very significant location.

Source: Scientific Reports

The Gyari site

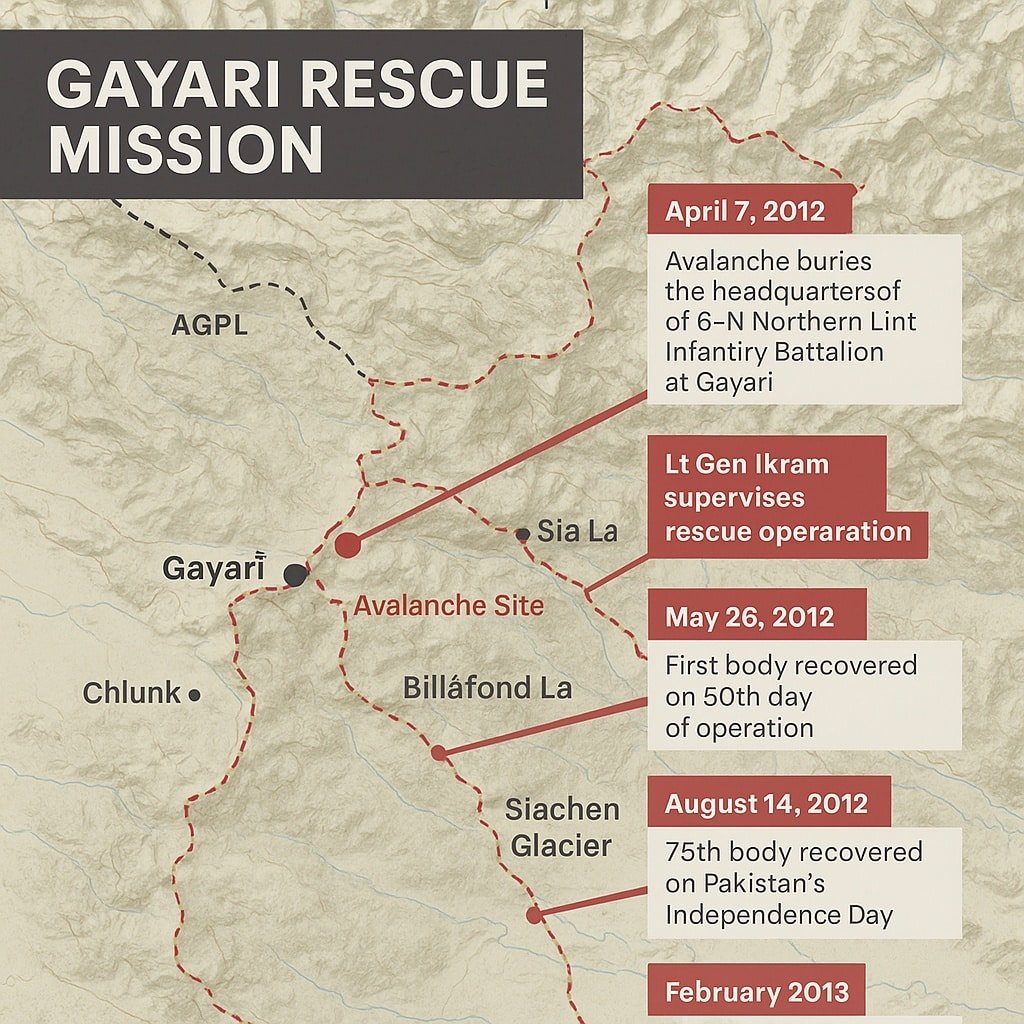

Gyari is nestled near the base of vertical, wall-like peaks. At 2 a.m. on the morning of April 7, 2012, an avalanche originated from the high snow buildups on these peaks. It was an unusually heavy winter. The avalanche covered an area of over 1 square kilometer, engulfing the entire battalion headquarters of the 6th Northern Light Infantry (NLI). Around 140 men, 124 of them soldiers and 11 civilians, were buried under 25-65 m of snow, rock, and debris. The incident appears to have occurred within a span of minutes. Sounds were heard at Goma, a remote post near Gyari. Still, the avalanche was only confirmed when calls to Gyari on PASCOM (a communication system used by the Pakistan Army) went unanswered. It was only after a search party was sent to Gyari in the early hours that the incident was confirmed.

Source: Scientific Reports

Initial Reactions

It had been established from the initial days of the recovery operations that there was no chance that those buried under the snow were alive. Col Sher Khan, an expert in mountain warfare who was sent by GHQ to oversee the rescue, had similar opinions. Geological experts, international disaster management teams, and experts from SUPARCO and SPD of Pakistan came to the site. Still, no one could come up with a reasonable plan to dig up the bodies or survivors, if any. Some believed that Gyari should be declared a mass grave site. Some sectors felt that maintaining a continued military presence at Siachen was futile.

You May Like To Read: Point NJ9842: Origins of Siachen Conflict and the Ambiguity of Demarcation

The Rescue Operation

Despite hopelessness surrounding the tragedy, the then Chief of Army Staff, Gen Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, flew in from Rawalpindi. I vowed in the presence of reporters on site that every single one of the bodies of Shuhada would be recovered. Maj Gen Ikram Ul Haq, Commander FCNA at the time, took charge of the search and rescue mission. The mission was the first of its kind: to clear debris of 20-25 million cubic feet of snow, ice, and rock at an altitude of 12,385 feet above sea level in an active, militarized glacial zone. Until heavy drilling machinery and equipment arrived from the Army Corps of Engineers, soldiers began digging with shovels, picks, and axes. The Army Medical Corps had set up a camp at Goma where bodies were sent. Samples were sent to MH Rawalpindi for DNA testing and confirming identity. Army Aviation helped in transporting heavy digging machinery on-site, and most of the machines, such as heavy bulldozers, had to be transferred through the difficult Khaplu-Goma route.

Thermal imaging, ground-penetrating radars, sniffer dogs, and remote sensors were used to challenge bodies. Most of the bodies were in good shape as the avalanche had occurred during the night when most of the troops were in their sleeping bags. The constant digging on site ran the risk of another avalanche and landslides. Winters brought in a break in the operation. Still, it continued in the spring and marked the resolve of the Pakistan Army and its men, who had aimed to honor the dead bodies of their fallen comrades and give them a proper burial in their respective hometowns. All 140 dead bodies were recovered in this operation that spanned over seven months.

Source: Wikipedia

The mountain did not just collapse on our soldiers—it collapsed on the nation’s soul. Yet our will was firmer than the ice.— Lt Gen Ikram Ul Haq (Retd.)

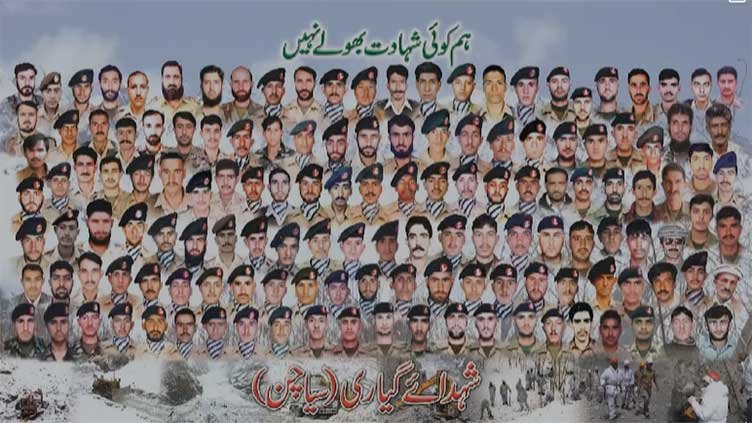

It was not just a rescue operation but a symbol of sheer willpower and grit displayed by the men of the Pakistan Army who understood the value of sacrifice for one’s nation and how it must be repaid. They truly embodied the phrase ‘no soldier must be left behind.’

Special thanks to Let Gen (R) Ikram Ul Haq, author of Moving The Mountain, Gyari-A Tribute.